In honor of Cephalopod Week, I’ve put together a short discussion on the types of ammonites typically found in Shaligrams. So, here we go!

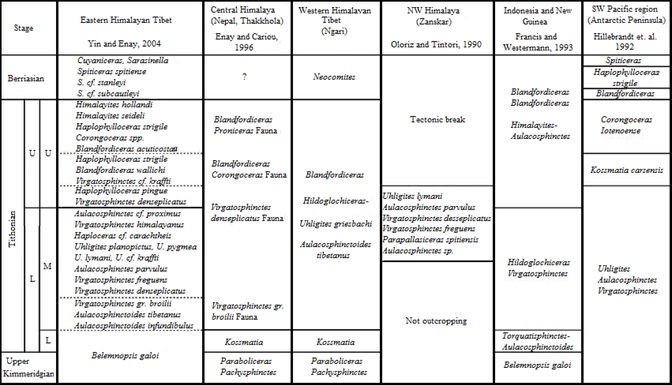

The Nepal Himalayas contain a wide variety of ammonite species owning to a number of different time periods, from M. bifurcatus and M. apertusmantataranus in the Ferruginous Oolite Formation,[i] to Kimmeridgian[ii] Paraboliceras assemblages, to late Tithonian-Berriasian Blanfordiceras and Proniceras assemblages. Shaligrams, however, are generally comprised of four particular species of Jurassic ammonites: Blandifordiceras, Haplophylloceras, and Perisphinctids (both Aulacosphinctus of the Upper Kimmeridgian/Lower Tithonian and Aulacosphinctoides of the Upper Tithonian). Other Shaligram formations include belemnites (such as the Ram Shaligram) and the bivalve Retroceramus (such as the Anirudda Shaligram) but for the most part, “classic†Shaligram manifestations are, by and large, comprised of various black shale ammonites at assorted levels of erosion and wear.[iii]

Blandfordiceras species (lower Tithonian age) are widely distributed ammonites especially known for their tight but evenly balanced spirals and raised, biplicate (Y-shaped), ridges. Geologist Herwart Helmstaedt (1969)[iv] was one of the first researchers to investigate the ammonites of the Thak Khola region (immediately south of Mustang) and, according to him, some fifty percent of all ammonites collected in Mustang belong to the Blandfordiceras genus. He is also credited with discovering and naming the new species Blandfordiceras muktinathense, though the name does not often appear in common usage (Dhital 2015: 288).

Haplophylloceras, on the other hand, tends to include fewer rings in the formation of its central spiral and sports a distinctive chevron-like ridge pattern along the outer phragmocone (the back edge of the shell). Finally, Perisphinctid ammonites are recognizable by their evolute shell morphology with typically biplicate, simple, or triplicate ribbing. Larger shells may have simple apertures and smooth body chambers while smaller species tend to have lappets and ribbed body chambers (Arkell et. al. 1957). Aulacosphinctoides, a member of the Perisphinctidae family, are also well represented in Shaligrams. These ammonites are characterized by an evolute shell with whorls broadly rounded, ribs sigmoid that mostly bifurcate (and occasionally trifurcate), and clearly defined lappets.[v] Aulacosphinctoides also closely resembles its Indo-Malagasian relative Torquantisphinctes but differs in that it has more rounded or depressed whorls and more sigmoid and frequently triplicate ribbing.[vi]

The paleontological history of ammonites in the Himalayas is a complex one and despite recent advances in the stratigraphical use of microfossil groups and non-palaeontological laboratory techniques in geological dating, ammonites continue to retain their pre-eminent position as one of the most reliable and accurate correlation tools available for marine Jurassic sequencing (not unlike dendrochronology to the archaeologist and paleo-ecologist). They also have a number of other uses.

Ammonites have been recognized for their value in palaeobiogeography studies and in the study of evolutionary mechanisms and patterns, such as speciation and extinction over vast expanses of geological time. As Kevin Page notes however, these latter studies are often hindered by incomplete understandings of ammonite correlation and taxonomy, from the species level upwards (2008: 54). This situation is then exacerbated by the limited funding available for such research given the preference amongst many funding organizations and media outlets for more mysterious or sensational fossil groups and more fashionable (if transient) scientific theories and hypotheses. This is why the Shaligram traditions of South Asia have something to offer the world of paleontology; adding new dimensions of interpretation and importance to the image of the ammonite, perhaps even to cultural conversations about the modern meanings of fossils as a whole. For Shaligram practitioners, the constant scientific debate and limited amount of concrete detail for describing Shaligram ammonites in Mustang is both taken in stride and as further evidence of the entanglements of different kinds of “storytelling†when it comes to Shaligram origins and ontologies. Or, as my old friend and mentor Prasad Vipul Yash once expressed it, “They don’t know and we don’t know. Not all of it, anyway. They call it one thing, we call it another, but it’s all the same thing. It just depends on what it is you want to know about the world.â€

[i] A thin (roughly 3 meter), black shale, marker bed which contains microscopic iron (ferruginous) particles which set it apart from the nearby Spiti Shales.

[ii] In the geologic timescale, the Kimmeridgian is a stage in the Late or Upper Jurassic epoch. It spans the time between 157.3 ± 1.0 Ma and 152.1 ± 0.9 Ma (million years ago). The Kimmeridgian follows the Oxfordian and precedes the Tithonian.

[iii] Similar looking ammonites which occasionally appear in Shaligram discussions (but are not considered Shaligram) are Dactylioceras semicelatum from Whitby, North Yorks England; Toxaceratiode sp. From the Walsh River, Queensland, Australia; Crucilobiceras densinodulum from Charmouth, Dorset UK; Dactylioceras athleticum from Schlaifhausen, Forscheim, near Nuremburg, Germany; and Acanthoceras sp from Agadir, Morocco.

[iv] H. Helmstaedt. 1969. Eine Ammoniten-Fauna aus den Spiti-Schiefern von Muktinath in Nepal. Zitteliana 1:63-88 [W. Kiessling/M. Krause]

[v] These are flanges that protrude from the final chamber at the front of the creature in adult male specimens [the microconch] which some speculate may have been used for sexual display. These features are not present on the larger female ammonites.

[vi] Sepkoski, Jack (2002). “Sepkoski’s Online Genus Database.” Retrieved 2016-09-14 and Phil Eyden (2003). “Ammonites: A General Overview.†Retrieved 2016-09-14.