Description:

As described in the Lakshmi-Narasimha Shaligram, Narasimha, or conversely Narsimha or Narsingh, is an avatar of Vishnu or Krishna who is considered to be the supreme God in certain traditions of Vaishnavism but is also a popular deity in Hinduism more generally. Narasimha commonly appears in early Hindu epics, iconography, and temple and festival worship and dates back to well over a millennium. Narasiṃha’s appearance is particularly distinctive, usually depicted as having a human torso and lower body with the head and arms of a lion. Narasimha is also colloquially referred to as the god of “in-betweens†given his most famous appearance as the ‘Great Protector’ of the devotee Prahlada or as the protector of all devotees in their times of need. For example, when Narasimha appeared to destroy the demon king Hiranyakashipu, he did so in such a way as to circumvent the demon’s boon not to be killed by any living being created by Brahma, not to be killed at night or by day, on the ground or in the sky, nor by any weapon, human, or animal. Narasimha thus appears as the blending of a man and a lion, at twilight, at the threshold of the courtyard, places Hiranyakshipu on his thighs, and disembowels him with his claws.

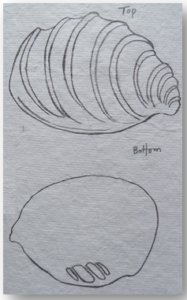

The general distinction between the Narasimha Shaligram and its more common counterpart, the Lakshmi-Narasimha Shaligram is in the presence of a “mouth†and “teeth†but without the inclusion of the two visible internal chakra-spirals.

For the most part, Narasimha Shaligrams are sought after for their highly protective qualities. As manifestations of Narasimha, the god who defends his devotees in their times of greatest need, Narasimha Shaligrams are said to bestow protection from theft or the influences of evil or impure persons. These Shaligrams are also said to aid in the healing of mental illnesses, especially anxiety and phobias, and to restore spiritual balance to persons caught in chaotic home situations. In some cases, Narasimha Shaligrams are also included in daily puja rituals for the sake of obtaining divine guidance before undertaking an especially challenging endeavor related to household or marital harmony.

In some Shaiva traditions, this Shaligram is interpreted as the deity Bhairava, a fierce and terrifying manifestation of Shiva associated with annihilation.

Vedic References: Praanatoshani Tantra pg. 347-348, Skanda Purana, Nagarekhanda, 244: 3-9, Brahmavaivartta (Prakritikhanda, Ch. 21), Garuda Purana (Panchanan Tarkaratna, Part 1, Ch. 45), Agni Purana; Bengavasi ed., Panchanan Tarkaratna, Saka 1812, Ch. 46

Vedic Description:

Large opening with two circular marks, glittering to look at (BV).

Mark of a mace at center, circular mark in lower middle, upper middle portion comparatively bigger (G).

(i) With a big opening and two circular marks.

(ii) With a long opening and linear marks resembling the mane of a lion, and also with two circular marks.

(iii) Marked with three dot-prints other things being the same as above.

(iv) Uneven in shape with a mixed reddish colour, having two big circular marks above it, and a crack at the front.

(v) Reddish in colour and printed with several teeth like marks, three or five dot-marks and a big circular mark.

(vi) With a big opening, a vanamala and two circular marks. This type is popularly known as Lakshminrisimha.

(vii) Black in colour with dot marks all over his body and two circular marks on His left side. This also is a variety of the Lakshminrisimha sub-type.

(viii) Printed with a lotus mark on His left side. This also is a sub-type of Lakshminrisimha.

(ix) When any of the above types of Narasimha is marked with five dot prints He is popularly called Kapilanrisimha.

(x) Printed with seven circular marks and golden dots and also having openings on all sides. This type is called Sarvotmukhanrisimha.

(xi) Variegated in colour, having many openings including a large one and marked with many circular prints. This type is popularly called Paataalanrisimha.

(xii) With two circular marks inside the main opening and eight others on His sides. This also is a variety of Paataalanrisimha.

(xiii) Aakaashanrisimha: With a comparatively high top and a big opening and also printed with circular marks.

(xiv) Jihvaanrisimha: Big in size, with two openings and two circular marks. He being the giver of poverty, His worship is forbidden.

(xv) Raakshasanrisimha: With a fierce opening and holes, and also marked with golden spots. His worship also is forbidden.

(xvi) Adhomukhanrisimha: With three circular marks one at the top and two on the sides, having His opening at the bottom.

(xvii) Jvaalaanrisimha: Marked with two circular prints and a vanamala, and having a small opening.

(xviii) Mahaanrisimha: Printed with two big circular marks and a few other linear marks one above the other. (P)

Narasimha Shaligram