Ato’dhisthana Vargesu Suryadisviva Murtisu |

Salagrama Silaiva Syad Adhisthanottamam Hareh

“The Lord resides in many places in which he may be worshipped, but of all the places Salagrama is the best.†– from Garuda PurÄṇa, Ch. 9, 1-23

Early one morning, late in the summer of 2016, I awoke just before sunrise and set out for the Kali Gandaki River. Clad in thick canvas pants and a pair of Vibram KSOs (well-suited as they were to walking around in fast-moving, shin-deep, river water), I made it a point to tie my Australian field hat securely to my head with a chinstrap before venturing out into Kagbeni’s lively pre-dawn streets. Since the wind was always threatening to steal the hat every time I turned my head, I figured that the discomfort of a spare bit of leather was a small price to pay against an afternoon burnt red in the glaring Himalayan sun. A mother and daughter in chubas, traditional Tibetan dresses, passed me cautiously, hunched over their hand brooms as they swept the previous day’s goat droppings from the cobblestones and out into the adjacent fields. An older Mustangi man, passing by with his caravan of mules and donkeys laden with rice and kerosene, shouted out a compliment. “Just like cowboys!†he yelled, touching his own imaginary brim. It was a typical morning in Kagbeni, filled with young women chatting on their way to fetch water from the village taps, small children playing in doorways, and the clink of copper cookware banging out breakfast in nearby guesthouse kitchens. I turned west and headed towards the roar of the water.

The Kali Gandaki river bed is nearly a quarter mile wide in most places around the village, and as the river slowly meanders back and forth across the valley, breaking up and remerging, undulating from bank to bank over the course of the day, it is continuously revealing a new landscape of stones and silt. The trick to finding Shaligrams, as one veteran pilgrim once taught me, was to first find one of the many small, shallow, side-streams branching off from the deep central currents. The best streams were the ones in the process of moving off course, easily identified by the tall banks of sediment actively breaking off and sliding down into the water below. Conversely, one could also seek out a stream that had recently petered out in favor of rejoining the main river and walk along its muddy edges slowly up-river, all the while keeping a sharp look-out towards any recently exposed areas.

As one picks their way carefully along through sun-warmed, clear waters, Shaligrams reveal themselves to the discerning eye. The constant flow of water combined with the settling of the heavy black silt grains that compose the Kali Gandaki are always exposing new stones, new pathways across the river bed, and new landscapes. Heraclitus was rather befitting when he said that, ‘No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.’[i] Apt in this regard, the Kali Gandaki renews its places of pilgrimage as often as it renews its arrival of pilgrims. I too was also discovering a new landscape, stepping out onto the very same riverbed I had visited just the day before but which now looked completely different—any familiar hills or rocks washed away in the night. Within a few minutes a Hindu pilgrim I had met previously in the week, a middle-aged Indian man dressed all in white, came up alongside me and asked if any Shaligrams had been revealed to me today. I smiled and replied that they hadn’t yet but that I was ready and the day was still young. He nodded. “DarÅ›an will come,†he said. “I am waiting too.â€

I was familiar with the practice of darśan from my time in India three years earlier. For Hindus, darśan is one of the most important aspects of ritual veneration, especially when it comes to the worship of murti, the sacred images and statues of Hindu deities present in homes and temples. Darśan is a Sanskrit word meaning “to see,†but this aspect of “seeing†does not just mean to see the deity physically. Darśan means to behold the deity as he or she truly is beyond the material form obvious to the eye and in return, to be beheld by the deity yourself. In other words, “seeing†is a form of direct contact between persons (human and divine) mediated by an exchange of gazes in the physical world but not limited to the material bodies involved. It is also a kind of knowing (Eck 1998: 2-5); through sight, both deity and devotee are said to participate in the essence of the other.

In the act of darÅ›an, the deity is an agent who “gives darÅ›an” (darÅ›an denÄ in Hindi), and it is the devotee who “takes darÅ›an” (darÅ›an lenÄ). In the views of many Hindus, God presents himself to be seen in material form because humans are, by their natures, limited to the use of their senses in order to apprehend the world they live in. Therefore, when a deity is present to offer darÅ›an, devotees arrive to “receive” what is given. What is given then is a kind of physical, bodily, and spiritual, interaction through the medium of the senses. Like the physicality of interacting with holy places, the dhams (the spiritual abode of the deity), the reciprocal gift-giving relationship in the darÅ›an draws on sense experience to construct a concrete, material, appearance of the divine through continuous cycles of relations and obligations exchanged through ritual. Not only does one “see” the deity and be “seen” in turn, one also “touches” the deity with the forehead and hands (sparÅ›a) and is “touched” as well. Devotees may also variously touch the limbs of their own bodies to establish the presence of certain aspects of the deity or to invite the deity’s attention to a particular physical issue or desire for contact. During the darÅ›an devotees also equally “smell” the incense and lotus flower perfumes and “hear” the sacred sounds of the mantras,[ii] the ringing of bells, and the blowing of the conch shell (Eck 1998: 11-12).

This “exchange of gazes” is then what enables a subject/object transformation where it often becomes unclear who is acting upon whom and in what capacity. Similar to Nancy Munn’s description of Aboriginal ‘transformations,’ where ancestor spirits produce material objects within which they are in some way embodied (1970), deities in the darÅ›an (Shaligrams included) demonstrate their own dynamic subjectivities in an association with an object world (1970: 143-147) that includes human bodies, ritual objects and other sacra, and landscapes. But Hindu deities are not only consubstantial with the objects they produce or inhabit, they are often described as being no different than them—their mythic presence and their material presence as one and the same thing. This is where the exchange or attribution of viewpoints also becomes possible; where the deities’ desires and actions are open to interpretation, ambiguous, and communally shared. For Shaligrams, darÅ›an constitutes the first vital link merging stone and body as well as between deity and fossil, a link that is initially established beginning with the physical movements and spaces of ritual.

Arrangements of darÅ›an altars (deities, deity accessories, miniature animals or people, photographs, sacred stones, etc.) are often carried out with the intention that each piece of the diorama can be connected to sacred texts, local events, household needs, and historical narratives that relate to the place or to the person that the altar currently serves. On an earlier trip to West Bengal, where I was first introduced to Shaligrams at the Radha-Krishna (Sri Sri Radha Madhava) temple in Mayapur, a local brahmacharya (celibate monk) once explained that his favorite stories involving Krishna’s pastimes were any one of the many tales of his days as a young cow-herder. During the middle of the day, when the temple darÅ›an altar was closed and veiled, he said that Krishna would then leave the temple at this time and engage in activities within the village dham, namely that he would re-enact his time as a cow-herder in the nearby goshala, where the sacred cows were kept. The brahmacharya often liked to represent these activities by placing small cow statues at the Krishna deity’s feet before closing the altar. For Shaligram devotees, the altar begins at the Kali Gandaki.

“I think that the river is like the flow of the mother,†commented a Hindu woman with a blue sari and a neat, white, bun sitting near the river banks. She held two small Shaligrams in her hand and, as I watched, began preparing a memorial puja ritual to mark the first anniversary of her own mother’s death[iii] and cremation. “It comes from the mountain. Shaligrams come from the mountain first. Then the river. I brought one Shaligram from my home here. It is Krishna Gopala; Krishna the infant with mother Yashoda. And then today another appears to me in Kali Gandaki. Now I have two Krishna Gopalas. This one you see,†she held the slightly larger of the two Shaligrams aloft, “this one is me just like I am with my mother. This one,†she now held aloft the other, “this one is my mother, who always worried after her children, letting me know she is with God. She is gone now, but I see her here. Krishna is here. She is here. I see them here, and they see me.â€

The complex mapping of kinship, deity, time, and distance was common among Shaligram practitioners who often described, as this woman did, a Shaligram as being both a manifestation of God (in this case, Krishna Gopala) as well as evidence of the presence of a deceased loved one. The “birth†of a Shaligram from the mountain and the river could be expressed both as a divine birth and as a representation of the devotee’s own birth, the birth of their families, or of specific children. But this layering of time in the context of mythic origin became even more complex within the relationships between Shaligram and devotee where, in the example above, the Shaligram is simultaneously Krishna as an infant in the presence of his mother Yashoda as well as the Hindu woman in the presence of her own mother now deceased. Unsurprisingly, several areas along the banks of the Kali Gandaki river are often used to perform death memorial pujas and more often than not, Shaligrams are incorporated. This begins the bridging of birth and death through the flow of the river which mirrors the bridging of birth and death in the familial genealogy (inheritance) of the Shaligram. In this case, an old Shaligram, passed from mother to daughter, was carried and worshipped by a woman who spent her lifetime as a doting mother to her children. Then, a new Shaligram is born out of the river, which becomes that same deceased mother’s care beyond death, encapsulated in the story of Krishna Gopala. Through the material linking of myth, ritual, and landscape, both the deity and the dead can then be “seen.†This practice of seeing and being seen by the deity (and the dead) is one of the most common, and most important, parts of ritual practice among observant Hindus and is, also, one of the major driving forces behind pilgrimage in Mustang, and throughout South Asia.

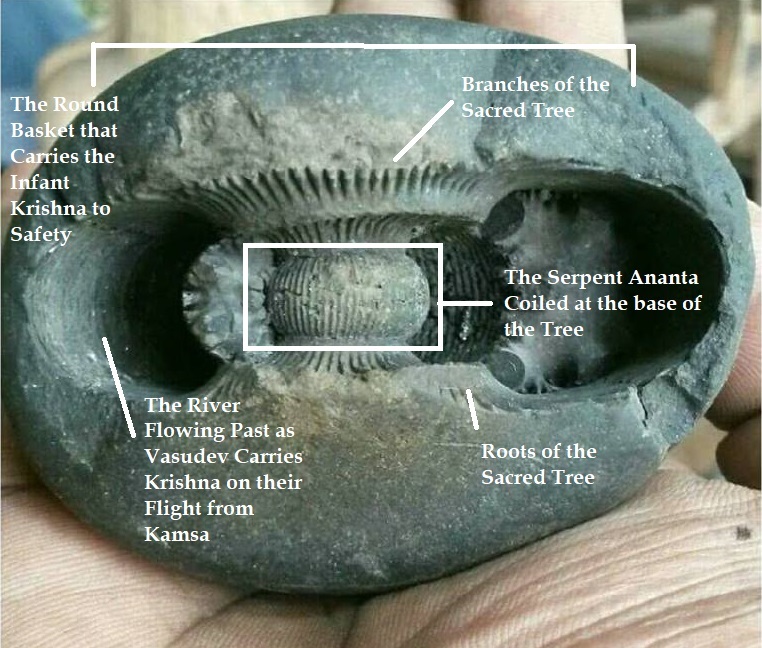

Searching for Shaligrams is its own kind of darśan. As I walked with particular care not to disturb too much sediment in the water, I noticed two especially important things about the experience I was undertaking. Firstly, the dark, almost inky, black color of a Shaligram is the first thing that tends to catch the seeker’s eye (since it stands out against a mix of silty grey and dirt brown); the second was the subtle appearance of ripples or spirals (the tell-tale ridges of the fossil ammonite shell) along an exposed surface that might indicate that a stone in question was, in fact, Shaligram. But not every stone that might initially appear this way was really Shaligram. Oftentimes, the refraction of light through the flowing water gave the impression of similar patterns on otherwise smooth stones and the accumulation of silt underneath the current was occasionally responsible for the appearance of analogous ridges in the sand that covered the river bed. More than once, a burst of excitement and a quick scoop of water to retrieve a Shaligram appearing in the riverbed would end with nothing more than a handful of sand and a plain rock.

Finding a Shaligram often left me with the sense of something truly born from the river, something which was appearing only at the very moment that I happened to see it. Carried down through millennia of time (or 175 million years if we’re going by geological counts) by an ancient and sacred tirtha (a Sanskrit term meaning “bridge/place of crossing/fordâ€) revealing itself just at that moment and just for me. Something that I was “seeing,†perhaps, that hadn’t been there a moment before. Tirthas often refer to places where the divine world and the physical world are closer together, and it is not unusual for important pilgrimage sites and sacred rivers throughout South Asia to be labeled as tirtha. Later on, I also found tirtha to be an apt concept for describing Shaligrams and Shaligram practices as a whole. In Western discourses, religion and science are often juxtaposed against one another. But among Shaligram practitioners, “deity†is equally “fossil,†and “stone†is also “body.†Nor do Shaligram devotees hybridize religion and science, as two possible if unrelated points of view regarding the essential nature of the same object, but instead, use them to draw links between two different ways of knowing. This is to say that, rather than describe a blending of separate, “purer,†forms of knowledge (as one might use syncretism to describe the blending of religious traditions), Shaligram practice demonstrates how Shaligrams as ammonites, Shaligrams as persons, and Shaligrams as deities constitute a shared reality.

_______________________________________________________________________

[i] Fragment 91, “Cratylusâ€

“Each time I remember Fragment 91 of Heraclitus: ‘You will not go down twice to the same river,’ I admire his dialectic still, because the facility with which we accept the first meaning (‘The river is different’) clandestinely imposes the second one (‘I am different’) and gives us the illusion of having invented it.†– Jorge Luis Borges, “New Refutation of Time,†Other Inquisitions.

[ii] The chanting of the mahamantra, for example, requires the repeated chanting of Krishna’s names and constitutes another instance in which one “sense aspect” of God is “no different” than another. Put another way, “seeing” God in the form of the deity is no different than “hearing” his name spoken or as Stephen Knapp explains: “The name Krishna is an avatara or incarnation of Krishna in the form of sound” (2011: pg 30).

[iii] In Nepal and India, a death anniversary is known as shraadh. The first death anniversary is called a barsy, from the word baras, meaning year in the Nepali and Hindi languages.

Shraadh means to give with devotion or to offer one’s respect. Shraadh is a ritual for expressing one’s respectful feelings for the ancestors. According to Nepali and Indian texts, a soul has to wander about in the various worlds after death and has to suffer a lot due to past karmas. Shraadh is a means of alleviating this suffering.

Shraddhyaa Kriyate Yaa Saa: Shraadh is the ritual accomplished to satiate one’s ancestors. Shraadh is a private ceremony performed by the family members of the departed soul. Though not mandated spiritually, it is typically performed by the eldest son and other siblings join in offering prayers together.