A few days ago, despite the monsoon rains, I was able to visit one of the ammonite fossil beds located a few hundred meters above the Muktinath Valley. The layer of fossils, the remnants of an ancient sea floor, sits up around 5000 meters and is slowly eroding out of the mountain to form a large wash of broken stones and fossil shells that extends some 300 meters down the mountain, slowly tumbling en masse towards the Thorong La river (which joins up with the Kali-Gandaki at Kagbeni a few kilometers to the south west). My purpose for visiting this particular fossil bed was two-fold: one, it allows me to observe the earliest geological processes that will eventually result in some of these ammonites becoming Shaligram and two, it gives me a chance to see unmodified structures in the stones that, given an additional few thousand years rolling through river silts, will become the characteristics of deities as read in the stones’ final manifestations. For example, one of my favorite Shaligrams is called Krishna Govinda (Krishna the Cowherder). It’s a typically palm-sized, smooth, and perfectly round black Shaligram which bears a white “cow hoof†impression on one side (an effect created by the breakage of a concentric quartz ring). As luck would have it, I was able to find just such a structure in one of the “raw†ammonites in this particular fossil wash-out as well. Naturally, many photos and comparisons followed.

_

At first glance, it may appear that my approach in this particular case is largely a scientific one; replacing religious interpretation with geological analysis; or “cow hoof†for “quartz erosion†to look at it another way. But my intent is not to replace one method of analysis with the other necessarily. Rather, one of the things I find most fascinating about Shaligram stones in general is their capacity to join scientific discourses with religious narratives, as opposed to assuming these interpretations to be mutually exclusive. Shaligram stones are ammonites and their geological history spans roughly 175 million years, through dozens of evolutionary taxonomies, and they provide us with a tremendous amount of information about the early ocean environments of ancient Earth. Shaligram stones are also the direct manifestations of divine movement in the form of deities of the Hindu pantheon, joining a physical landscape to a sacred landscape and linking individuals and families to profound cultural histories and ritual practices that have been in use for at least 4000 years. In other words, not only have Shaligrams passed down through eons of wind, river currents, and tectonic uplift but they have also equally passed down through inheritance, births, deaths, marriages, and pilgrimage. A Shaligram is not a Shaligram absent either one of these threads. In short, Shaligram stones exist at a juncture wherein Science and Religion are having a very fascinating conversation with one another, in particular, a conversation about what it means “to be†something. This is how Shaligrams can be both ammonite fossil and divine manifestations, just as rivers can be both vital economic and social waterways emerging out of the glacial melt and tirthas (bridges) into the sacred world of gods and goddesses.

_

Shaligrams are largely venerated by Vaishnava Hindus (devotees of the god Vishnu) and one of the defining characteristics of Vishnu’s story is the theology of the Dasavatara, or the 10 incarnations of Vishnu. In this particular aspect of Vishnu’s lengthy mythological history, is it said that he has appeared on Earth in some form on 10 separate occasions (or will, given that we are currently only up to 9 in the 10 avatar stretch). This does not mean, however, that each avatar was human (or even human-looking); rather each avatar took on a specific form and function designed to accomplish some particular set of tasks necessary for the given time in which the avatar appeared. Given the circumstances of his appearance, Vishnu has manifested as a fish (Matsya), a tortoise (Kurma), a boar (Varaha), a half-man half-lion (Narasimha), a dwarf-man (Vamana), a warrior bearing an axe (Parashurama), Sri Ram the god-king of Ayodhya, Krishna the divine lover and hero of the Mahabharata, the Buddha (depending on what tradition you come from, there is some contention on this one. As some traditions place other famous gurus or teachers in this position), and finally Kalki, the destroyer of the current age who is yet to come. Given all this, one might imagine that becoming a stone can’t really be all that difficult in the grand scheme of omnipotence (though I must save discussion of the many Shaligram origin stories for another post).

_

Unsurprisingly, the Dasavatara are also represented in Shaligrams. There are Matsya Shaligrams and Kurma Shaligrams, Ram Shaligrams and Krishna Shaligrams, each appearing according to the characteristics laid out in the Puranas and in the Epic stories of the exploits of the Dasavatara. But what is more, I can’t help but notice that we live in a time where the narratives of religion and science are increasingly at odds, and they are certainly fighting about much more than ammonites. Both religion and science have become a part of the political project, in service to various agendas seeking national or geo-political power. As such, they are pitted against one another as two presumptive sides to the same Almighty Dollar coin. Religion is poised to reject Science, and Science employed to tear down Religion. So the more I think on it, perhaps Shaligrams, just as all the rest of the incarnations of Vishnu, have arrived both as fossil and as deity, in just the right form for what this time needs most.

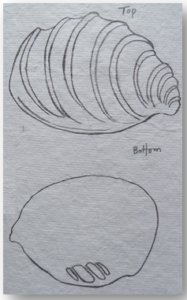

Another ammonite fossil emerging out of the erosion wash.

A quartz structure in a “raw” ammonite fossil resembling a “cow hoof”

Fossil wash-out near Jhong village.

Hard at Work

Ammonite fossils — Kshetra Shaligram (Mountain-born Shaligram)